Citizen Science and Gaelic in Scotland: A Literature Review

Research by Lisa MacDonald for Ulluminate.

February 2024

This Literature Review explores the thematic focus of the inaugural Ulluminate science festival in Ullapool in 2024. Our community-led, place-based event is supported by the New Voices Grant as part of the Highlands and Islands Climate Change Community Researcher Network. The programme, which is funded by UKRI and co-delivered by BSA and Science Ceilidh, seeks to build capacity at a local level to enable communities to lead on research related to climate change and resilience.

The vitality of Gaelic in the local community over the past two centuries can be visualised as an inverted bell curve, its fall and rise caused by power dynamics played out through the proxy of language ideology. Economic and political oppression coupled with demographic shifts led to a state of near extinction, but language revitalisation policies and innovative resources have resulted in an overwhelming majority of children in the local primary school in Gaelic rather than English medium education, as well as a significant number of adults at various stages of an enthusiastic learning journey. Ulluminate sought to explore the ways in which it is possible to seed Citizen Science projects in the cultural soil of the indigenous linguistic environment, and it is their symbiotic interplay which will be investigated below.

The potentialities of Gaelic and Citizen Science intertwined can be discovered by first reviewing the literature concerning Citizen Science in and of itself, before considering its role within a democratising ontology: what is the truth, and who holds it? A decolonising approach shifts the prevailing discourse by deconstructing narratives of minority language and marginalised histories. Contemporary writing on the subjects of empowerment and sustainability in Gaelic Scotland supports a re-examination of indigenous knowledge.

A growing body of academic literature describes the relatively new field of Citizen Science.

Mahr et al. (2018) trace its origins from the pre-professional engagement of the 1700s to more recent participatory movements, particularly relating to environmentalism and conservation. They observe that ‘science and society were inseparable’ (p. 104). Bonney et al. (2016) suggest that the ‘central tenet of citizen science is opening access to the scientific enterprise’ (p. 3). Farr, Ngo and Olsen (2023) refer to multiplicity of benefits: participants gain new knowledge and skills, enjoy the social aspect, and make a contribution to science through low-cost generation of large amounts of data, both longitudinally and over a wide geographic area, whilst raising public awareness of the research.

Citizen Science research projects relating to the natural world, and to ornithology in particular, have proved highly successful (Chunming, 2018; RSPB, no date; BBC, no date), having ‘contributed much to our knowledge of […] birds through the years’ (Coldren, 2022, p. 2). The research impact is significant: ‘all these programs have allowed a greater understanding of the status and long-term health of avian populations, and this knowledge can be important for informing decisions and strategies for management and conservation of populations’ (Coldren, 2022, p. 2). In this way, Citizen Science projects make an important contribution to sustainability, biodiversity and policy change. However, Varga et al. (2023) point out that this can only be achieved ‘with an inclusive mindset and with constant efforts to involve a fair representation of society’ (p. 6). Herein lies a challenge: there is significant concern that entire communities and cultures are missing from Citizen Science engagement, and that this represents a missed opportunity for those communities, particularly in terms of empowerment and capacity building, as well as for wider scientific data collection (Benyei et al., 2023). For a variety of reasons ranging from practical considerations of infrastructure and language to persistent colonising attitudes, ‘indigenous knowledge is not valued, or simply not available, in decision-making processes (Stephenson & Moller, 2009, p. 112). However, research shows Indigenous and Local Knowledge (ILK) to be highly reliable: ‘over a range of birds, mammals and plants, ILK documented and validated with focus groups provides similar abundance indices of wild species to trained scientists undertaking transects’ (Danielsen et al., 2018, p. 119). As Vitos (2021) understood, ‘local and indigenous communities often possess unique knowledge about the natural resources on which their livelihoods depend’ (p. 228). For this reason, ‘growing acceptance of different forms of knowledge means that geographic citizen science is seen as a promising solution to achieve long-term management of key environments with greater respect for, and an active role accorded to, local communities’ (Vitos, 2021, pp. 228-229).

Although it cannot be said that the Gaelic community is hard to reach logistically nor linguistically in the way Benyei et al. (2023) describe monolingual minority language communities in infrastructure-poor areas in East Africa, the notion of ‘remoteness’, particularly when viewed from the conurbations of the Central Belt or further south, is commonly encountered in public discourse (The Scotsman, 2016), to the great chagrin of those who live there (Meek, 2023). There is anecdotal evidence that researchers feel poorly equipped to understand the customs, traditions and dynamics of rural communities, and many research projects are not linguistically equipped to access the Gaelic part of the bilingual and bicultural identities of these communities. This is further explored by Hunter (2014), as he notes that modern environmental thinking has often been shaped in Edinburgh, ignoring local Highlanders’ views, and thus creating two quite different perspectives of the land and its future. Notable exceptions are specific corpus building and heritage projects such as DASG and Tobar an Dualchais, which seek to preserve the remaining cultural heritage after generations of atrition. Baldwin (1994) warns that ‘not only does precious little now survive of the Gaelic and culture but what does remain has largely ‘gone underground’. […] Recollection and understanding of the old ways, where this survives, is now largely fragmentary, and it has been submerged by new cultural waves with quite different cultural roots and aspirations’ (pp. 295-296).

Alongside these real challenges, a strand of thoughtful writing considers alternative ways of being. As McIntosh (2020) suggests,

Ecology is the study of plant and animal communities. Communities are about relationships. Just as you can have mouse or giraffe ecology, so human ecology studies interactions between the social environment and the natural environment in which we live; you could say, between human nature and natural nature. Anthropogenic climate change – that which has its ‘genesis’ or origins in the ‘anthropos’, or human domain – can only be understood in such a framework (p. 2).

He builds on the notion that the damage inflicted on nature, on humankind and on culture requires redress, and that this ‘cultural healing entails coming alive to community with one another, with the place where we live, and with soul’ (McIntosh, 2001, p. 2). Rennie (2020) echoes the research findings described above, which relate to the benefits of communities’ self-image and agency when their indigenous knowledge is respected:

With the DNA of buntanas – the cumulative awareness of belonging to a place […] – comes the responsibility of trust and respect for that place. This belies the myth that rural communities are backwards looking. It simply reiterates a different vision for the future, in which the legacy of past human interactivity with place can suggest alternative means for securing the resilience of future communities (p. 184)

As McIntosh (2001) puts it, ‘when we used to do things right we never questioned why we did them so. It had to go wrong before we could understand why the old folk’s ways were right. The challenge of today is to become ecologists again, but this time to be so consciously’ (p. 41). Hunter (2014) raises the possibility of ‘the Gaelic-speaking world having long-ago anticipated modes of thought which we mostly categorise as relatively recent’ (p. 59) as he describes the deep love and minute observation of nature contained within the Gaelic tradition of poetry and song, linking this spiritual connection from the early Christian monks via the great bardic schools to modern ecologists such as Frank Fraser Darling. McIntosh (2020) picks up on the role of artists, poets and musicians and their response to climate change: they are ‘opening up avenues of inner life that flow through into outer life. The survival of being, at least as expressed in the fulness of human being, rests on lubrication between those two’ (p. 190).

This work of expressing deep connection has been ‘particularly evident […] in the relationship between Gaels and their natural environment’ (Hunter, 2014, p. 65). The Gaelic literary tradition is replete with sincere and elegant nature poetry, much of which continues to be sung in the traditional style to this day. Donnchadh Bàn, or Duncan Bàn MacIntyre, (1724 – 1812) from Gen Orchy in Argyll exemplifies this body of work perfectly, both in praise of his native county and in his descriptions of the natural world around him:

Bha eòin an t-sléibhe ’nan ealtainn ghléghlain

A’ gabhail bheusan air ghéig ’sa’ choill;

An uiseag cheutach ’s a luinneag féin aice,

Feadan spéiseil gu réidh a’ seinn;

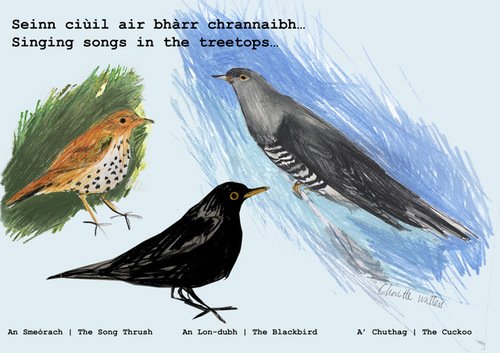

A’ chuthag ’s smeòrach am bàrr an ògain

A’ gabhail òrain gu ceòlmhor binn;

’N uair ghoir an cuanal gu loinneil guanach

’S e ’s gloin’ a chualas am fuaim ’sa’ ghleann.

The birds of the heath, in pure, bright flocks,

were singing melodies on woodland bough,

the winsome skylark hath her special warble,

beloved chanter playing fluently;

on the top of sapling, the cuckoo and the mavis

sing a tuneful and sweet refrain;

when the choir piped up, blithely and gaily,

the finest music heard was their chorus in the glen.

(Macleod, 1952, pp. 170-171)

This cultural repository of praise for the natural environment is deeply rooted in the collective Gaelic identity. As McIntosh (2008) states, ‘what you are is your community. You absorb a lot from your landscape and an awful lot from the people you live with. You might not be aware of it at the time – you might even scorn it – but you are absorbed in it’ (p. 79). A fascination with songbirds is evidenced throughout this cultural inheritance, and Caimbeul (2005) has reproduced many traditional chants which perfectly imitate the sounds of song thrushes and other familiar birds. The cuckoo’s presence is by no means restricted to the Gaelic tradition. The ornithologists Brown & Warren (2011) ask who among us ‘has not rejoiced at the call of the first spring cuckoo’ (p. 6). However, they warn that the cuckoo ‘joined the red list of the Birds of conservation concern because of the halving of their populations over the last 25 years’ (Brown & Warren, 2011, p. 5). Amongst the reasons for this dramatic and alarming decline, habitat changes, land use and food availability are cited, but it is clear that ‘migration has always been a hazardous affair for birds, and at a time when 43 per cent of Europe’s birds qualify as Species of European Conservation Concern, migratory birds seem to be shouldering more of this pressure than other groups’ (Brown & Warren, 2011, p. 5). These migratory challenges are further described by the British Trust for Ornithology (no date), who draw attention to thrush movement as researched within a Citizen Science project.

With regard to specific Gaelic projects, there appears to be a gap in knowledge, as well as in the data. However, this could be overcome through engagement from inside a ‘supportive community’ (Liberatore et al., 2018, p. 1). Such a Community of Practice (Wenger et al., 2002) may be geographically challenging to create, but there are suggestions that modern technology could be helpful in this regard. Straub (2016) suggests a chat forum, while Liberatore et al. (2018) consider more commonly used social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, which ‘can create a virtual space where participants can learn from each other and share stories, ideas, and experiences. Social media also allows participants to stay engaged […] throughout the year, a challenge for once-a- year citizen science efforts (p. 2).

To summarise, the literature suggests that indigenous knowledge is highly valuable in Citizen Science projects, both to enhance data collection and to return agency to marginalised cultures. Furthermore, it shows that the Gaelic tradition holds a rich carrying stream with regard to its natural environment, exemplified by a particular appreciation of song birds in metaphoric and literal meanings. This presents a unique opportunity for a multi-layered project with the potential to enrich the life of a small Highland community in a holistic and lasting way.

References

Baldwin, J. (1994) ‘At the Back of the Great Rock: Crofting and Settlement in Coigach, Lochbroom’ in J. Baldwin (ed.) Peoples & Settlement in North-West Ross. Edinburgh: School of Scottish Studies.

BBC (no date) Gardenwatch. Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/4gjThGt61ndDfXqcWL04rqn/gardenwatch-now-closed-to-submissions. Accessed 15 November 2023

Benyei, P., Skarlatidou, A., Argyriou, D., Hall, R., Theilade, I., Turreira- García, N., Latreche, D., Albert, A., Berger, D., Cartró-Sabaté, M., Chang, J., Chiaravalloti, R., Cortesi, A., Danielsen, F., Haklay, M., Jacobi, E., Nigussie, A., Reyes-García, V., Rodrigues, E., Sauini, T., Shadrin,

V., Siqueira, A., Supriadi, Tillah, M., Tofighi-Niaki, A., Vronski, N. and Woods, T. (2023) ‘Challenges, Strategies, and Impacts of Doing Citizen Science with Marginalised and Indigenous Communities: Reflections from Project Coordinators’ in Citizen Science: Theory and Practice, 8(1): 21, pp. 1–15. DOI: https://doi. org/10.5334/cstp.514

Bonney, R., Cooper, C. and Ballard, H. (2016) ‘The Theory and Practice of Citizen Science: Launching a New Journal’ in Citizen Science: Theory and Practice, 1(1): 1, pp. 1–4, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/cstp.65

British Trust for Ornithology (no date) Winter Thrushes Survey. Available at https://www.bto.org/our-science/projects/winter-thrushes-survey/resources/migration-images. Accessed 25 October 2023

Brown, A. & Warren, M. (eds) (2011) There And Back? A celebration of Bird Migration. Peterborough: Langford Press.

Caimbeul, T. (ed.) (2005) Air do Bhonnagan a Ghaoil. Stornoway: Acair.

Chunming Li, C. (2018) ‘Citizen science on the Chinese mainland’ in S. Hecker, M. Haklay, A. Bowser, Z. Makuch, J. Vogel and A. Bonn (eds) Citizen Science: Innovation in Open Science, Society and Policy. UCL Press, London. https://doi.org/10.14324 /111.9781787352339

Coldren, C. (2022) ‘Citizen Science and the Pandemic: A Case Study of the Christmas Bird Count’ in Citizen Science: Theory and Practice, 7(1): 32, pp. 1–9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/ cstp.473

DASG (no date) Dachaigh airson Stòras na Gàidhlig. Available at https://dasg.ac.uk. Accessed 15 November 2023

Danielsen, F., Burgess, N., Coronado, I., Enghoff, M., Holt, S., Jensen, P., Poulsen, M. and Rueda, R. (2018) ‘The value of indigenous and local knowledge as citizen science’ in S. Hecker, M. Haklay, A. Bowser, Z. Makuch, J. Vogel and A. Bonn (eds) Citizen Science: Innovation in Open Science, Society and Policy. UCL Press, London. https://doi.org/10.14324 /111.9781787352339

Farr, C., Ngo, F. and Olsen, B., (2023) ‘Evaluating Data Quality and Changes in Species Identification in a Citizen Science Bird Monitoring Project’ in Citizen Science: Theory and Practice, 8(1): 24, pp. 1–13. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/cstp.604

Hunter, J. (2014) On the Other Side of Sorrow: Nature and People in the Scottish Highlands (1st edn). London: Birlinn Limited.

Liberatore, A., Bowkett, E., MacLeod, C., Spurr, E. and Longnecker, N. (2018) ‘Social Media as a Platform for a Citizen Science Community of Practice’ in Citizen Science: Theory and Practice, 3(1): 3, pp. 1–14, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/cstp.108

Macleod, A. (ed) (1952) The Songs of Duncan Bàn Macintyre. Edinburgh: Scottish Gaelic Texts Society.

Mahr, D., Göbel, C., Irwin, A. and Vohland, K. (2018) ‘Watching or being watched:

Enhancing productive discussion between the citizen sciences, the social sciences and the humanities’ in S. Hecker, M. Haklay, A. Bowser, Z. Makuch, J. Vogel and A. Bonn (eds) Citizen Science: Innovation in Open Science, Society and Policy. UCL Press, London. https://doi.org/10.14324 /111.9781787352339

Meek, R. (2023) ‘Where and what should be defined as ‘remote’ is key for rural Scots’ in The National. Available at https://www.thenational.scot/politics/23825271.defined-remote-key-rural-scots/. Accessed 15 November 2023

McIntosh, A. (2001) Soil and Soul: People versus Corporate Power. London: Aurum Press.

McIntosh, A. (2008) Rekindling Community: Connecting People, Environment and Spirituality. Totnes: Green Books.

McIntosh, A. (2020) Riders on the Storm: The Climate Crisis and the Survival of Being. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

Rennie, F. (2020) The Changing Outer Hebrides: Galson and the meaning of Place. Stornoway: Acair.

RSPB (no date) Big Garden Birdwatch. Available at https://www.rspb.org.uk/whats-happening/big-garden-birdwatch. Accessed 15 November 2023

Straub, M. (2016) ‘Giving Citizen Scientists a Chance: A Study of Volunteer-led Scientific Discovery’ in Citizen Science: Theory and Practice, 1(1): 5, pp. 1–10, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/cstp.40

The Scotsman (2016) Where can you find Scotland’s remote villages? Available at https://www.scotsman.com/arts-and-culture/where-can-you-find-scotlands-remote-villages-1485169. Accessed 15 November 2023

Tobar an Dualchais (no date). Available at https://www.tobarandualchais.co.uk/. Accessed 15 November 2023

Varga, D., Doran, C., Ortega, B. and Segú Odriozola, M. (2023) ‘How can Inclusive Citizen Science Transform the Sustainable Development Agenda? Recommendations for a Wider and More Meaningful Inclusion in the Design of Citizen Science Initiatives’ in Citizen Science: Theory and Practice, 8(1): 29, pp. 1–10. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/ cstp.572

Vitos, M. (2021) ‘Lessons from Recording Traditional Ecological Knowledge in the Congo Basin’ in A. Skarlatidou and M. Haklay (eds) Geographic Citizen Science Design. London: UCL Press.

Wenger, E., McDermott, R. and Snyder, W. (2002) Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Managing Knowledge. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Press.